2 per cent of Kenyans own over half of the country’s arable land - KHRC report

A KHRC report finds less than two per cent of Kenyans control over half of arable land, worsening food insecurity, weakening county revenues and deepening economic inequality nationwide.

Less than two per cent of Kenyans own more than half of the country’s arable land, leaving millions of smallholders and young people locked out of opportunities to build wealth, access credit and secure livelihoods.

The Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), in its new report, says this extreme concentration of land is driving food insecurity, limiting agricultural productivity and reinforcing long-standing economic and social inequalities.

More To Read

- Factory farming in Africa: Development banks see it as a good idea, but it’s bad for the climate

- AU calls for rapid tech adoption in farming to shield continent from food crises

- Ruto unveils Sh400 billion mega dam plan to turn North and Coast regions into Kenya's new food basket

- International Rescue Committee warns millions at risk as drought intensifies across Northern Somalia

- City Hall moves to recognise urban farmers in policy review

- Agrifood SMEs to benefit from new Sh16.4 billion funding programme

The report, "Who Owns Kenya?", links the country’s wider economic crisis to deep-rooted land inequality, noting that land remains Kenya’s most valuable resource yet is concentrated in the hands of a small elite.

According to the findings, fewer than two per cent of Kenyans control more than half of the country’s arable land, much of it either idle or acquired through irregular means.

By contrast, 98 per cent of all farm holdings, mainly small plots averaging 1.2 hectares, occupy just 46 per cent of farmed land. Only 0.1 per cent of large-scale landholders, with farms averaging 77.8 hectares, hold 39 per cent of the total land under cultivation.

The report says this imbalance continues to deny millions the chance to secure livelihoods because it suppresses agricultural productivity, worsens food insecurity and prevents young people and women from owning land or using land titles to access credit.

It also ties the problem to Kenya’s hunger situation, noting that 2.2 million people are currently facing acute food insecurity, with the country scoring 25 on the Global Hunger Index-classified as “serious”.

KHRC further warns that community land remains especially vulnerable. Slow registration processes, forged titles, boundary manipulation and politically driven evictions have continued to expose communities to exploitation.

The Coast region is highlighted as one of the most affected areas, with more than 65 per cent of residents in Kilifi, Kwale and Lamu lacking formal land titles, leaving families trapped as squatters on ancestral land.

“These counties consistently record below-average performance in health, education and income indicators,” reads the report.

Despite land’s immense economic value, the report says land-based taxes contribute less than one per cent of county revenue in most devolved units. Large landowners continue to benefit from weak taxation systems, outdated valuation rolls, political interference and deliberate under-assessment of property values.

“High-value locations such as Karen and Muthaiga in Nairobi and Diani, Mtwapa and Watamu at the Coast, have been undervalued for decades, allowing wealthy owners to pay significantly less than they should,” the report states.

It notes that Kenya effectively operates two economic systems: one for the wealthy, who enjoy expansive land ownership, political protection and minimal taxation and another for ordinary citizens, who face heavy taxes on basic goods and income but receive diminishing public services.

KHRC argues that land remains central to resolving these inequalities. It recommends a robust and progressive land value tax to discourage speculation, reduce land hoarding, lower prices, unlock idle land for productive use and expand county revenue. Estimates in the report indicate that taxing wealth could raise Sh125 billion, almost double the current allocation for social protection.

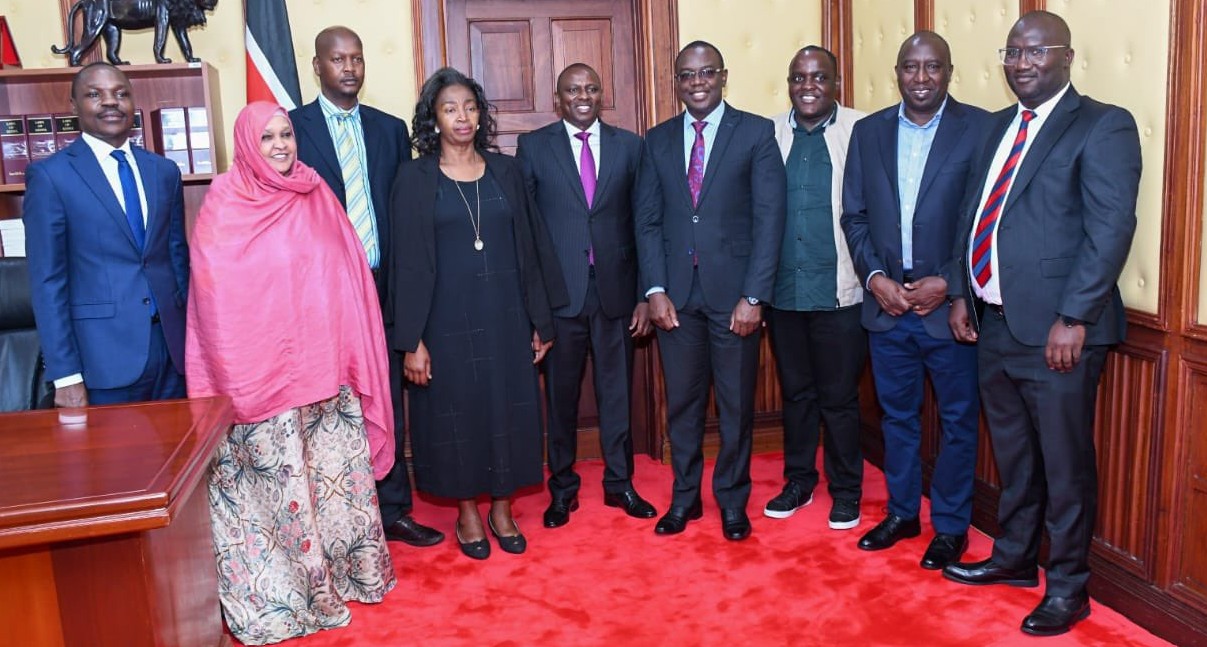

“Kenya needs economic decisions that put people first, protect rights and ensure fair distribution of national resources. This includes reducing waste and corruption, managing debt responsibly, strengthening transparency, reforming land taxation, and supporting communities that have been ignored or displaced,” KHRC executive director Davis Malombe said.

Other Topics To Read

The report traces present-day inequalities to a history of land dispossession. It notes that colonial authorities forcibly displaced communities, redrew boundaries and allocated vast tracts to settlers and their allies. Independence did not reverse these injustices; instead, political families and their networks inherited much of the land previously taken by the colonial state.

To date, land ownership remains the single biggest source of wealth, political influence and opportunity in Kenya.

“Any conversation about fairness or economic justice must therefore begin with land,” reads the report.

It further argues that Kenya’s political economy is built around land, with existing systems continuing to favour a small elite. While ordinary citizens pay high taxes on consumption and income, wealthy landowners hold vast tracts, sometimes idle or irregularly acquired, without contributing proportionately through taxation.

“Land-related wealth remains largely untaxed, even though it forms the bulk of elite wealth,” reads the report.

The report emphasises that land value taxation (LVT), if properly implemented, offers one of the most equitable and sustainable ways for the country to raise revenue.

“It would generate predictable funding for essential services including healthcare, education and social protection, while reducing reliance on regressive taxes such as VAT, which disproportionately burden low-income households,” KHRC said.

It further says a progressive land tax would curb speculation, encourage productive land use, ensure wealthier landowners contribute fairly, strengthen counties’ revenue autonomy and support restorative justice.

It adds that fairer land taxation would also improve transparency by forcing disclosure of beneficial land ownership, a key step in dismantling secrecy around illicit wealth.

Only 20 per cent of Kenya’s land is arable or suitable for productive use, with about 75 per cent of the population living in these high-potential areas. Scarcity and unequal distribution have long driven conflict among individuals, communities and institutions seeking to secure livelihoods.

Landlessness averages 30 per cent nationally and is closely linked to poverty and lower life expectancy.

Small land sizes below five hectares are associated with poverty and reduced well-being because they are not economically viable under current farming practices. Larger, secure land holdings, on the other hand, correlate positively with higher incomes, lower poverty levels and longer life expectancy.

While attempts have been made to regulate landholding sizes, including the Minimum and Maximum Land Holding Acreage Bill of 2015 and its 2023 version, both faced opposition in Parliament and stalled.

The National Land Commission (NLC) has continued attempts at reform, but implementation remains limited.

Top Stories Today